Nomadicine is a new feature of HealthHippieMD that redefines wellness travel, not just as a luxury escape, but as intentional healing through place. Blending evidence-based science with soulful storytelling, Nomadicine explores how environment, awe, culture, and connection can rewire our nervous systems and restore well-being. It’s medicine without the white coat—delivered through immersive journeys, grounded insights, and human connection.

In this inaugural entry, I write about my trip to Australia in 2013—not because it was perfect, but because it captured so many of the elements I now recognize as essential to real, restorative travel. It wasn’t a wellness retreat or a vacation. It was work and play, challenge and ease. I was there for a professional project, but what stayed with me had almost nothing to do with deliverables. It was the people, the conversations, the landscape, the food, and the way time moved differently.

I’m using that trip as a kind of straw man—not to say “do this,” but to ask: what about that experience that felt so nourishing? What made it stick? And can we recreate pieces of that in other places, or even closer to home? Australia isn’t the model so much as the mirror. It gave me language and questions for what it means to feel well while moving through the world. That’s where Nomadicine begins.

Travel is not an Escape—It is a Return to Wholeness

Somewhere between a long conversation over barramundi and a dusty Shiraz outside Adelaide, I remembered something I had not felt in years: joy without striving. It is not the kind that shows up in lab results or habit trackers, but the quieter kind woven from friendship, curiosity, and the way good food tastes when nobody is in a hurry.

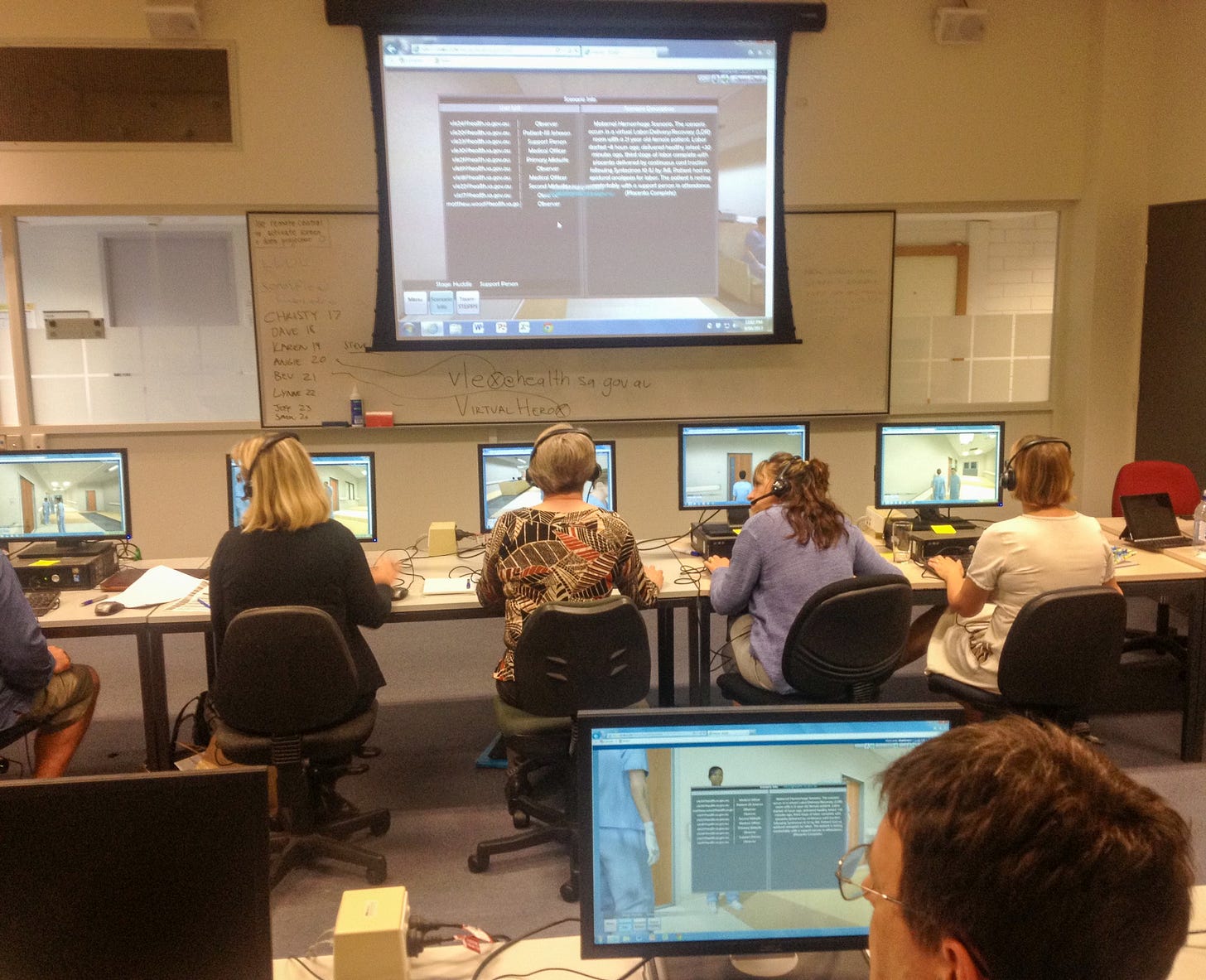

I traveled to Australia on a professional invitation, part of a South Australian government-sponsored initiative to deploy a game-based learning platform for distance medical education. It was the kind of opportunity that would look impressive on a CV, but that is not why I still think about it.

What stayed with me had less to do with the project's success and more with how the place and its people disarmed me.

Adelaide unfolded as a place of paradoxical magic: intellectually stimulating, culturally distinct, yet strangely familiar. The eucalyptus-lined roads and golden light felt like echoes of Northern California, but the rhythm of life was different—more spacious, more relational. My days moved fluidly between high-stakes conversations with university faculty and long, quiet walks through the Botanical Gardens, where the air seemed to slow my thinking.

I fed kangaroos at Cleland Wildlife Park and made eye contact with dingos, and held a koala in a moment that felt oddly spiritual. Something is grounding about touching the Earth in a different hemisphere—about realizing how much is happening without you and how much you might be missing while staring at your inbox.

The professional aspects of the trip were deeply fulfilling—brilliant, thoughtful colleagues and honest dialogue about the future of medicine and education. However, the fundamental reset came between the meetings: dinners that turned into long evenings of laughter and wine, conversations in hotels (their name for pubs) that moved between philosophy, ethics, politics, healthcare systems, and favorite recipes. One night, after a day of wine tasting in Barossa Valley, we ended up at a tucked-away restaurant that served one of my favorite dinners ever. That day, sun-soaked vineyards, warm hospitality, and a table with friends talking about real things without performance lodged in my brain as an indelible memory.

Another night, I was invited to my host's home for dinner with her family. We sat around her table, sharing food prepared with love but without fuss. I was just…part of it. I was not an outsider, not a visitor, just another voice at the table. That, too, was a kind of healing.

I loved Australia so much that one of my daughters started calling me an "Australian Weaboo." For context, weaboo is a slang term that originated to describe non-Japanese people obsessed with Japanese culture, often to an exaggerated or idealized degree. It has since evolved into a playful shorthand for anyone with a slightly embarrassing obsession with another culture. Guilty as charged! I returned home quoting Aussie slang, changed my Siri voice to an Aussie-accented woman, and surreptitiously Googled real estate in Adelaide. However, beneath the humor was a truth: the place had gotten under my skin like few other destinations.

The Case for Leaving Home

In modern medicine, we obsessively track inputs: protein grams, sleep cycles, VO₂ max. However, what if one of the most powerful wellbeing variables is not a substance or behavior but a place?

In 2019, researchers at the University of Exeter found that people who spent just two hours a week in natural settings reported significantly better health and wellbeing (White et al., 2019). Two hours—the length of a movie or a leisurely lunch in town. The takeaway? Environment shapes us biologically, emotionally, and spiritually. Travel, when intentional, can definitely be medicine.

Neuroscience explains part of it. Novelty activates the hippocampus, enhancing learning and memory (Lisman & Grace, 2005; Kafkas & Montaldi, 2018). As psychologist Dacher Keltner and others have shown, awe can reduce activity in the brain's default mode network, dampening one's internal monologue and enhancing feelings of connection to the world (Van Elk et al., 2019). The cultural contrast, the unfamiliar sights, the accents, the landscapes that look like home but are not—these are not just scenic. They are neurologically stimulating.

Reclaiming Wellness from the Spa Brochure

Let us pause here and define terms. I'm not planning a "detox in Bali" wellness series. I am not against luxury, but I am interested in experiences beyond the silk robe and cucumber water chaser.

As I have come to understand, wellness is not about indulgence. It is about integration—a pulling back together of parts we did not realize had fractured—our internal rhythms, wholeness, and sense of belonging. I plan to write about the kind of travel that will not just reset your calendar. Hopefully, it will reset your entire way of being.

In Australia, that reset came to me not from a structured retreat or bio-hacked itinerary but from a sequence of ordinary but opportune moments: petting a koala, hearing didgeridoos at dusk, belly-laughing with strangers who started to feel like family. These were not bucket-list items. They were touch-points of belonging in a foreign land—to place, to people, and, in the moment, to myself.

The 8 Pillars of Travel-Inspired Wellness

Throughout this ongoing series, I will use the 8 Pillars of Wellness as a framework adapted from Margaret Swarbrick's work (Swarbrick, 2006). Think of them less as categories and more as a tuning fork. Every place I explore will resonate differently:

Physical – Movement, rest, nourishment

Emotional – Expression, regulation, connection

Spiritual – Awe, purpose, presence

Environmental – Nature, rhythm, place

Intellectual – Learning, curiosity, perspective

Social – Belonging, conversation, friendship

Occupational – Alignment, creativity, meaningful contribution

Financial – Simplicity, stewardship, values-based choices

Not every journey will activate all of these, but the best ones-the ones we remember years later—often come close.

Australia touched nearly every dimension of wellness in ways I had not anticipated. Physically, I walked for miles daily—through university corridors, a bustling downtown, and the Adelaide Botanic Gardens, where the warm air and flowers made each breath feel medicinal. Emotionally, I was nourished by connection: lingering dinners with new friends, open-hearted conversations that skipped small talk and dove straight into the good stuff. Spiritually, I found awe in quiet moments—a koala's stillness, the staggering beauty of a beach at dusk, the way a family welcomed me into their home as if I had always belonged. Environmentally, the land itself worked on me: the dry warmth, the Southern Hemisphere light, the subtle song of unfamiliar birds. Intellectually, the trip was a feast—seminars on medical education by day, philosophical debates over wine by night. Socially, I felt folded into a generous and unhurried life rhythm, where relationships mattered more than agendas. Occupationally, I experienced what it is like to do meaningful work in alignment with values, using creativity and innovation in the service of learning and health. It was a full-spectrum experience, and I did not even realize how much I needed it until I returned home.

That trip did not change my life in any cinematic way. However, it centered me in my life—more attuned, balanced, and present.

The Unspoken Science of Place

Let us take a moment to appreciate what extraordinary beings we are. Your skin feels the native humidity. Your gut recalibrates to local microbes (David et al., 2014). Your circadian rhythms and hormones respond to the city's beat, loud traffic, and the walking environment. Every time you travel, your entire physiology is learning a new song.

Shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, is well-known in Japan as a clinical intervention. Being in a forest lowers cortisol, heart rate, and blood pressure (Park et al., 2010; Hansen et al., 2017). They do not use the same term in Australia, but I practiced my version in the hills above the Cleland sanctuary, where tall trees framed views of the valley, and the animals watched you with casual disinterest.

Moreover, do not underestimate the power of awe. Studies show that awe-inspiring experiences increase altruism and decrease narcissistic behaviors (Piff et al., 2015; Stellar et al., 2020). This is not just about feeling small in a big world. It is about reorienting your nervous system toward connectedness and wonder. We forget ourselves just enough to remember we are part of something larger.

What to Expect from Nomadicine

Nomadicine is not a guidebook. But, you WILL find field notes—dispatches from places where something clicked, where I or a reader felt reconnected to their senses, where food and conversation felt medicinal, where walking in unfamiliar environments or hearing the cadence of another country's humor remind me or others that presence is the most renewable resource we posess.

You will hear how place shapes people and how people, in turn, learn to live in harmony with place. Some stories will come from far-flung corners. Others may be closer to home. All will ask: What does feeling well in a world designed for speed and disconnection mean?

Your Turn: Where Did You Heal?

I would love for this to be more than a monologue. So here is my question to you:

Where did you feel most like yourself?

Where did something in you awaken? Where did you remember how to breathe more slowly or laugh more easily?

Reply to this post or email me directly (jeffrey.taekman@heathhippiemd.com). I would love to hear your story—and, with your permission, maybe share it in a future edition. Let us create our atlas of healing.

Until then, travel well. And stay curious.

— Jeff Taekman, M.D., HealthHippieMD and Nomadicine

References

White, M. P., et al. (2019). Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 7730. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-44097-3

Lisman, J. E., & Grace, A. A. (2005). The hippocampal-VTA loop: controlling the entry of information into long-term memory. Neuron, 46(5), 703-713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.002

Kafkas, A., & Montaldi, D. (2018). How do memory systems detect and respond to novelty? Neuroscience Letters, 680, 60-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2018.01.053

Van Elk, M., et al. (2019). Neural correlates of the awe experience: Reduced default mode network activity during awe. Human Brain Mapping, 40(12), 3561-3574. Link

Park, B. J., et al. (2010). The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 15(1), 18-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-009-0086-9

Hansen, M. M., et al. (2017). Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(8), 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080851

Piff, P. K., et al. (2015). Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000018

Stellar, J. E., et al. (2020). Awe as a collective emotion: An ecological approach to awe experiences in collective gatherings. Nature Communications, 11, 4389. Link

Swarbrick, M. (2006). A wellness approach. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29(4), 311-314. https://doi.org/10.2975/29.2006.311.314

David, L. A., et al. (2014). Host lifestyle affects human microbiota on daily timescales. Genome Biology, 15(7), R89. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2014-15-7-r89

Be inspired. Be informed. Be Well.

Want more stories and science on travel, wellness, and the art of presence?

Subscribe to the newsletter or email me your story.